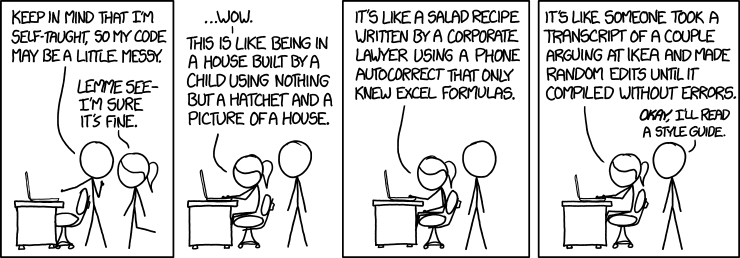

As a beginner developer working on pet projects at home, it's easy to argue that once code goes through the compiler, it's all the same. Right?

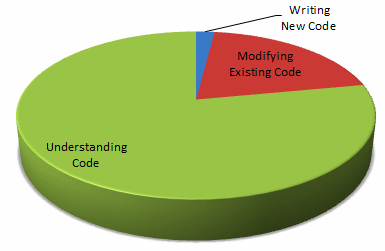

The flaw in this argument is that it assumes that all software developers do is write new code. The reality is that we actually spend much more time reading and modifying existing code than writing new code.

For this reason, code cleanliness and readability are paramount to project success. More important than your framework choice, test coverage percentage or project management solution, is the cleanliness and readability of your code.

The seminal MIT textbook Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs sums it up perfectly:

Programs must be written for people to read, and only incidentally for machines to execute

Clean code matters to project success because starting a project quickly is rarely the problem; it's finishing quickly that's hard. As the cyclomatic complexity of your app increases, it becomes more and more difficult to add new features and diagnose bugs. It also becomes harder for programmers who are not specialists to make meaningful contributions to your project. Bad code compounds these issues. If you can't read the code, how can you understand what it's doing?

For this reason, the most important book I have ever read as a programmer is Clean Code by Robert C. Martin. Everyone who writes code should read this book.

I could write a second book just pointing out all the great parts of the first book. But for now, I'd like to reflect on my favorite five quotes from the first five chapters. I hope these quotes will inspire you to push yourself and your team towards better, more maintainable code.

Chapter 1 - Clean Code

"You know you are working on clean code when each routine you read turns out to be pretty much what you expected."

– Ward Cunningham (inventor of Wiki)

If I had to pick a favorite quote from the book, this would be it. Clean code does what you'd expect it to do. In many ways, every other sentence in the book is just an attempt to clarify this concept.

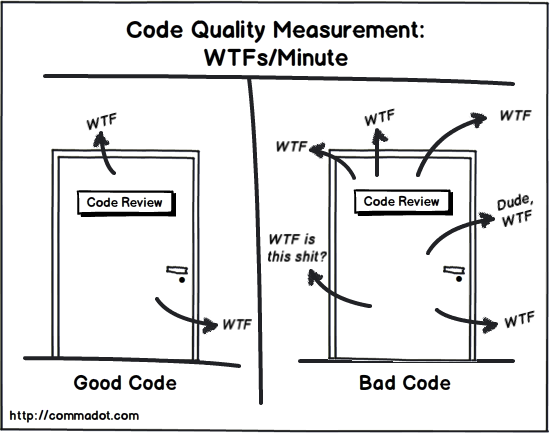

But how can you know what the reader expects your code to do? Grab a friend and do a code review.

Take note of what makes sense to them right away, and what makes them say "WTF". If you get a lot of "WTFs", your code is not clean. Let's look at some more quotes from the book to identify common causes of "WTF".

Chapter 2 - Naming

"Programmers must avoid leaving false clues that obscure the meaning of code... Do not refer to a grouping of accounts as an

accountListunless it's actually a List. The word means something specific to programmers. If a container holding the accounts is not actually a List, it may lead to false conclusions. So accountGroup or bunchOfAccounts or just plain accounts would be better."

Most programmers know to stay away from poor variable names like one or two character names (e.g. a1) or undescriptive placeholders (e.g. mystring). But an overly descriptive name can be just as bad or worse. If you call a variable thingHashMap and a year later your team decides to model "things" as a tree map instead, all of a sudden the variable name isn't just useless, its actually harmful.

Choose names that describe what the content does, not what it is.

Chapter 3 - Functions

"Functions should do one thing. They should do it well. They should do it only."

Take a look at this example Spring MVC controller method:

@RequestMapping(value = {"/"})

public ModelAndView execute() {

ModelAndView mav = new ModelAndView();

URL url = new URL("http://example.com");

HttpURLConnection con = (HttpURLConnection)

url.openConnection();

con.setRequestMethod("GET");

con.setRequestProperty("Content-Type", "application/json");

BufferedReader in = new BufferedReader(

new InputStreamReader(con.getInputStream()));

String inputLine;

StringBuffer content = new StringBuffer();

while ((inputLine = in.readLine()) != null) {

content.append(inputLine);

}

con.disconnect()

mav.add("content", content);

return mav;

If you take 20 or so seconds, you can parse through this code block to understand the basic control flow:

- Instantiate a ModelAndView object

- Get content from

example.comand put it into the ModelAndView object - Return the ModelAndView object

But when reading the code, there are all kinds of other details that distract from that main purpose, e.g.

- Modeling the URL as a Java object

- Casting the connection to the right type

- Setting request method and headers

- Setting up a BufferedReader to parse the response

etc etc.

A reader can understand the control flow once they figure out which lines are details and which lines are important, but that takes unnecessary effort, and someone who isn't well versed in Java might get bogged down trying to understand what's happening here.

Now consider this refactored version, which accomplishes the same thing:

@RequestMapping(value = {"/"})

public ModelAndView execute() {

ModelAndView mav = new ModelAndView();

mav.add("content", getExampleContent());

return mav;

}

Even though this refactored version looks radically different, it still accomplishes the same control flow:

- Instantiate a ModelAndView object

- Get content from

example.comand put it into the ModelAndView object - Return the ModelAndView object

The difference is that it only explicitly describes the important parts. The name of the method getExampleContent() tells the reader what is happening without bogging them down with the details. If they need to know how it works under the hood, they can jump to that method definition.

A well written main method should read like a story. Just like each of the methods it executes, it should do one thing, do it well, and do it only: execute the right methods in the right order.

Chapter 4 - Comments

"When you find yourself in a position where you need to write a comment, think it through and see whether there isn't some way to turn the tables and express yourself in code."

Comments seem like a great way to make code more readable, but they can be dangerous as well. Why is this? Uncle Bob explains it best:

Because they lie. Not always, and not intentionally, but too often. The older a comment is, and the farther away it is from the code it describes, the more likely it is to be just plain wrong. The reason is simple. Programmers can't realistically maintain them."

My rule of thumb is as follows:

A comment is helpful if it describes what the code is used for. A comment is harmful if it describes how the code works.

Do write comments that describe what your class represents, what problems it solves, etc. Do not write comments explaining the control flow of your code. Comments that explain "how" your code works are an indication that your code isn't clean.

If you need to explain why you've defined a variable or what a for loop is doing, write a named function instead. Document your code with your code.

Chapter 5 - Formatting

"Code formatting is important. It is too important to ignore and it is too important to treat religiously. Code formatting is about communication, and communication is the professional developer's first order of business."

When different blocks of code in the same project look different, it causes the reader to wonder whether the differences are functional or stylistic. This is bad, because it increases cognitive overhead.

Imagine a legacy Javascript project with single quotes in one file and double quotes in another. When reading through that project for the first time, it’s natural to wonder whether the double quotes are there for a reason, or if one programmer just preferred them.

Your reader should never have to ask this question, because it unnecessarily increases the overhead required to understand the project. If you're constantly forced to manually separate style differences from functionality in your brain, you're wasting energy on making a distinction that should have been made by the author.

As an author, don't make your reader work any harder than they already have to. It doesn't really matter what your style rules are - just pick some and be consistent. The best way to do so is by codifying them into linter rules and enforcing them at build time.

I hope these tips have inspired you to push yourself and your team towards better, more maintainable code. If you haven't yet read Clean Code by Robert C. Martin, you should pick up the book as soon as possible. It made me a better programmer, and it can make you a better programmer too.