A note to the reader: For explanation on how to set up the lab environment see the "Introduction" section of the post.

If you're looking for a specific phase:

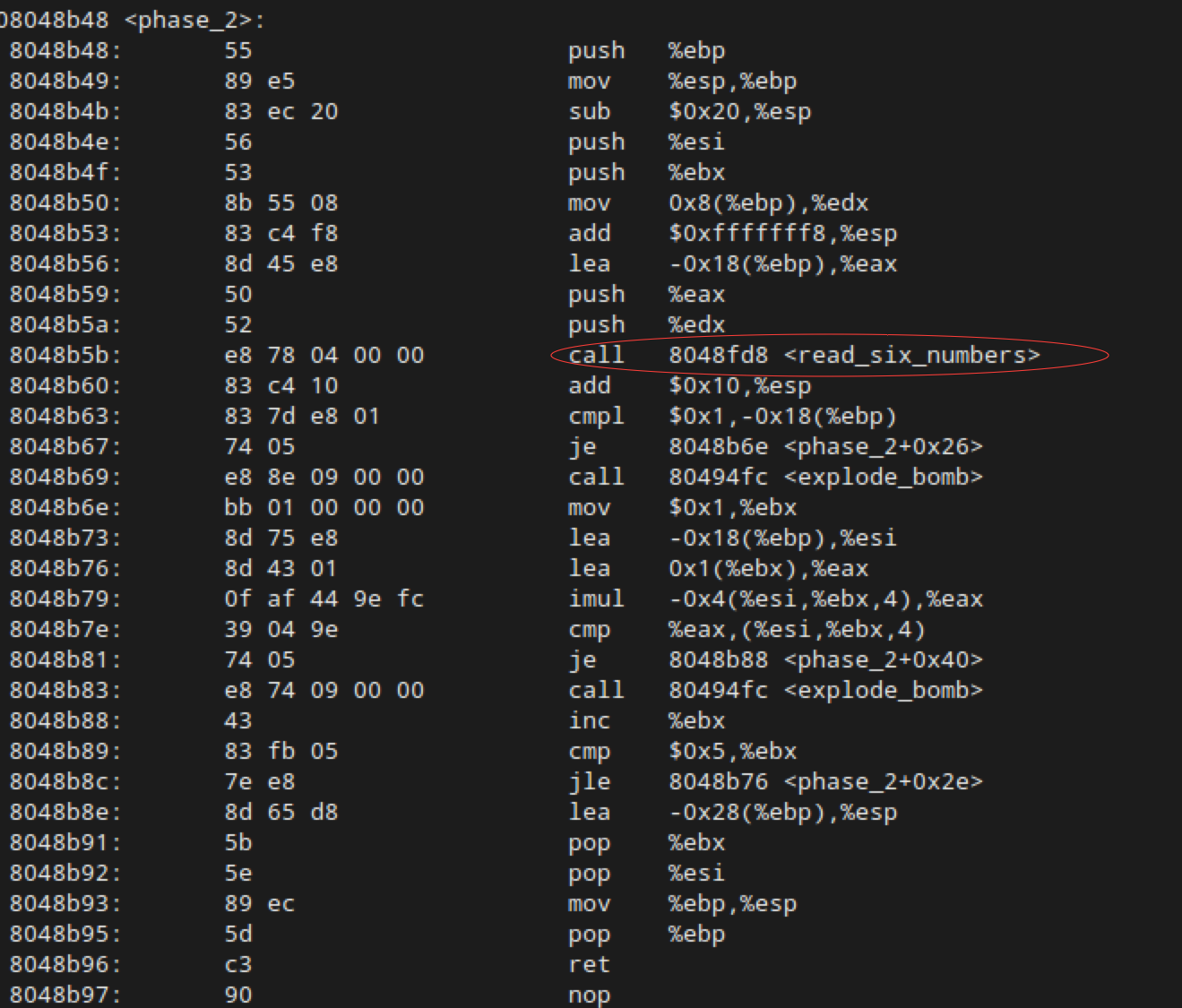

Ok, now things get a lot more interesting a lot more quickly. Let’s get started the same way we did last time, by looking at our objdump file for clues:

The first thing to notice here is that <phase_2> is calling a function by the name of <read_six_numbers>. If we really wanted to be pedantic, we could go take a look at this function, but for the sake of brevity in this already very long tutorial, I’m going to go ahead and tell you that it looks to make sure the stdin input has six integers in it, each separated by a space. So there’s our first big clue: our answer takes the format a b c d e f where a-f are integers.

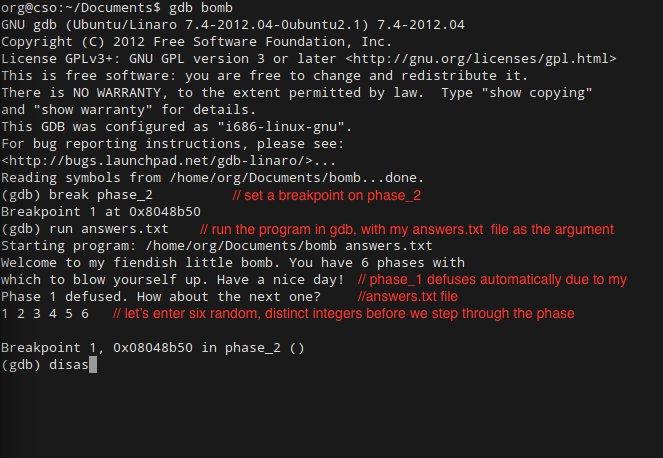

Now that we know roughly what our input should look like, let’s fire up gdb and do a little reverse engineering to figure out which six integers we should be inputting.

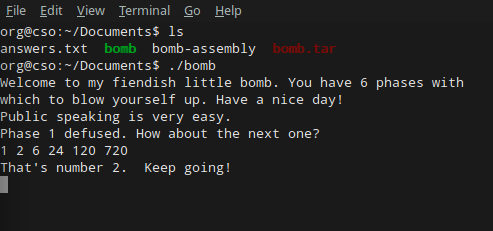

Sidenote: Typing in every passphrase every time we run the bomb gets really annoying really quickly. The bomb is written in such a way that it accepts a text file as an input. You can add your passphrases to this text file, separating each by a newline, and pass it to the bomb binary as an argument to avoid typing everything out every time you run the program. That’s what I’ll be doing from now on. See the lab handout for more information.

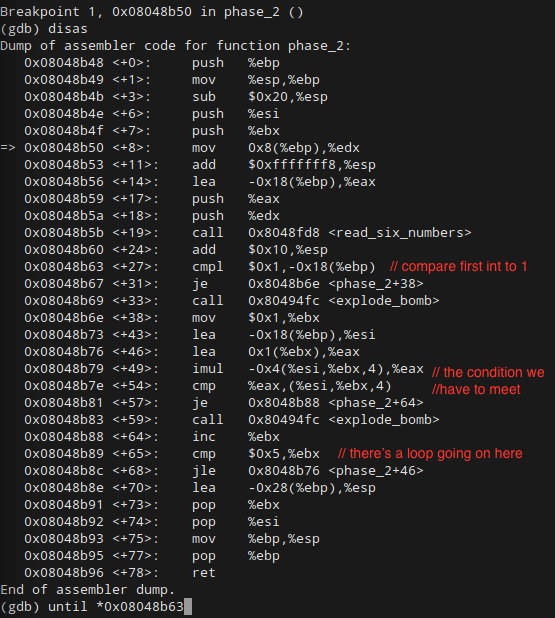

Now that we’re stopped at our breakpoint, let’s run disas to take a look at the assembly code and see if we can’t figure out exactly what’s going on. The output will look something like this:

Assuming you know assembly language basics (if you don’t, stop now and study up), a few things should jump out at you right away. Before anything else happens, a number is getting compared to 1, and the bomb is going off this number isn’t also 1. This means that the first integer in our secret phrase is undoubtedly 1.

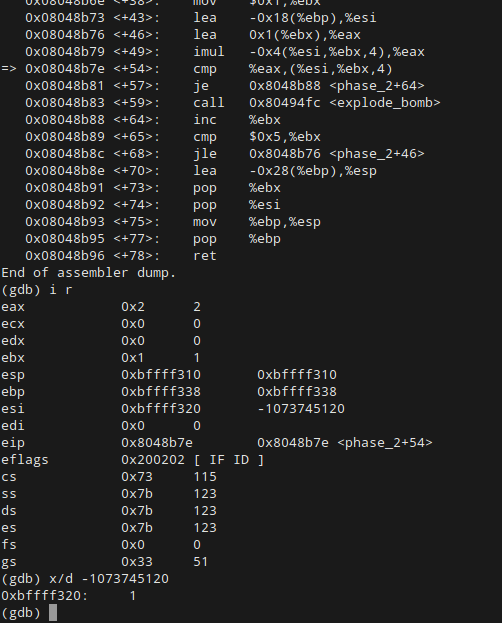

The second thing to note is that the function is looping over its input. After %eax is compared to (%esi, %ebx, 4) at <+54>, %ebx gets incremented and, as long as its less than 5, the function jumps back to above the comparison so that it can do it again. This means that our input integers will probably be a pattern of some sort, where <+46> is where the math that increments the pattern happens. Let’s use until to jump down to the comparison and see if we can’t suss out what our second input number should be:

Once we’ve arrived at the comparison statement, we can use the i r command to see the contents of our registers. %eax, which is the register to which our value is being compared, is equal to 2. Therefore, the second integer in our passphrase should be 2.

The simplest way to solve this level completely is by continuing to step through the code, seeing what %eax is equal to after each iteration. Next you’ll find 6, then 24, then 120 followed by 720. If you’re really smart, however, you’ll notice that the assembly code is actually implementing the following algorithm:

v[0] = 1

v[i] = (i+i) * v[i-1]

Either way, the second passphrase ends up being 1 2 6 24 120 720.

On to the next challenge!